[ad_1]

Bird flu cases have more than doubled in the country within a few weeks, but researchers can’t determine why the spike is happening because surveillance for human infections has been patchy for seven months.

Just this week, California reported its 15th infection in dairy workers and Washington state reported seven probable cases in poultry workers.

Hundreds of emails from state and local health departments, obtained in records requests from KFF Health News, help reveal why. Despite health officials’ arduous efforts to track human infections, surveillance is marred by delays, inconsistencies, and blind spots.

Several documents reflect a breakdown in communication with a subset of farm owners who don’t want themselves or their employees monitored for signs of bird flu.

For instance, a terse July 29 email from the Weld County Department of Public Health and Environment in Colorado said, “Currently attempting to monitor 26 dairies. 9 have refused.”

The email tallied the people on farms in the state who were supposed to be monitored: “1250+ known workers plus an unknown amount exposed from dairies with whom we have not had contact or refused to provide information.”

Other emails hint that cases on dairy farms were missed. And an exchange between health officials in Michigan suggested that people connected to dairy farms had spread the bird flu virus to pet cats. But there hadn’t been enough testing to really know.

Researchers worldwide are increasingly concerned.

“I have been distressed and depressed by the lack of epidemiologic data and the lack of surveillance,” said Nicole Lurie, formerly the assistant secretary for preparedness and response in the Obama administration.

Bird flu viruses have long been on the short list of pathogens with pandemic potential. Although they have been around for nearly three decades in birds, the unprecedented spread among U.S. dairy cattle this year is alarming: The viruses have evolved to thrive within mammals. Maria Van Kerkhove, head of the emerging diseases unit at the World Health Organization, said, “We need to see more systemic, strategic testing of humans.”

Refusals and Delays

A key reason for spotty surveillance is that public health decisions largely lie with farm owners who have reported outbreaks among their cattle or poultry, according to emails, slide decks, and videos obtained by KFF Health News, and interviews with health officials in five states with outbreaks.

In a video of a small meeting at Central District Health in Boise, Idaho, an official warned colleagues that some dairies don’t want their names or locations disclosed to health departments. “Our involvement becomes very sketchy in such places,” she said.

“I just finished speaking to the owner of the dairy farm,” wrote a public health nurse at the Mid-Michigan district health department in a May 10 email. “[REDACTED] feels that this may have started [REDACTED] weeks ago, that was the first time that they noticed a decrease in milk production,” she wrote. “[REDACTED] does not feel that they need MSU Extension to come out,” she added, referring to outreach to farmworkers provided by Michigan State University.

“We have had multiple dairies refuse a site visit,” wrote the communicable disease program manager in Weld, Colorado, in a July 2 email.

Many farmers cooperated with health officials, but delays between their visits and when outbreaks started meant cases might have been missed. “There were 4 people who discussed having symptoms,” a Weld health official wrote in another email describing her visit to a farm with a bird flu outbreak, “but unfortunately all of them had either already passed the testing window, or did not want to be tested.”

Jason Chessher, who leads Weld’s public health department, said farmers often tell them not to visit because of time constraints.

Dairy operations require labor throughout the day, especially when cows are sick. Pausing work so employees can learn about the bird flu virus or go get tested could cut milk production and potentially harm animals needing attention. And if a bird flu test is positive, the farm owner loses labor for additional days and a worker might not get paid. Such realities complicate public health efforts, several health officials said.

An email from Weld’s health department, about a dairy owner in Colorado, reflected this idea: “Producer refuses to send workers to Sunrise [clinic] to get tested since they’re too busy. He has pinkeye, too.” Pink eye, or conjunctivitis, is a symptom of various infections, including the bird flu.

Chessher and other health officials told KFF Health News that instead of visiting farms, they often ask owners or supervisors to let them know if anyone on-site is ill. Or they may ask farm owners for a list of employee phone numbers to prompt workers to text the health department about any symptoms.

Jennifer Morse, medical director at the Mid-Michigan District Health Department, conceded that relying on owners raises the risk cases will be missed, but that being too pushy could reignite a backlash against public health. Some of the fiercest resistance against covid-19 measures, such as masking and vaccines, were in rural areas.

“It’s better to understand where they’re coming from and figure out the best way to work with them,” she said. “Because if you try to work against them, it will not go well.”

Cat Clues

And then there were the pet cats. Unlike dozens of feral cats found dead on farms with outbreaks, these domestic cats didn’t roam around herds, lapping up milk that teemed with virus.

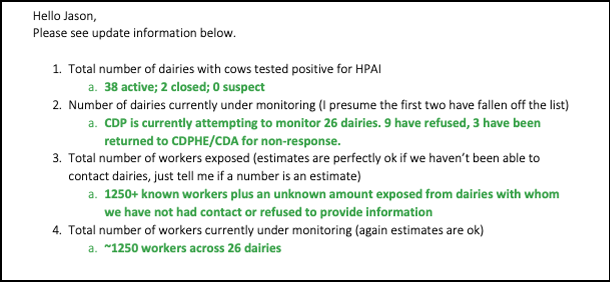

In emails, Mid-Michigan health officials hypothesized that the cats acquired the virus from droplets, known as fomites, on their owners’ hands or clothing. “If we only could have gotten testing on the [REDACTED] household members, their clothing if possible, and their workplaces, we may have been able to prove human->fomite->cat transmission,” said a July 22 email.

![A screenshot of an email that reads: "Subject: RE: HPAI domestic cats manuscript / YES I am 100% interested in this and think I vocalized previously that more should be said about this. Happy to do whatever possible to help! I think it is absolutely fascinating and if we only could have gotten testing on the [REDACTED] household members, their clothing if possible, their workplaces, we may have been able to prove human -> fomite -> cat transmission… / Jennifer Morse, MD, MPH, FAAFP / she/her/hers / Medical Director / Central Michigan District | Mid-Michigan District | District Health Department #10”](https://kffhealthnews.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2024/10/Monitoring02.png)

Her colleague suggested they publish a report on the cat cases “to inform others about the potential for indirect transmission to companion animals.”

Thijs Kuiken, a bird flu researcher in the Netherlands, at the Erasmus Medical Center in Rotterdam, said person-to-cat infections wouldn’t be surprising since felines are so susceptible to the virus. Fomites may have been the cause or, he suggested, an infected — but untested — owner might have passed it on.

Hints of missed cases add to mounting evidence of undetected bird flu infections. Health officials said they’re aware of the problem but that it’s not due only to farm owners’ objections.

Local health departments are chronically understaffed. For every 6,000 people in rural areas, there’s one public health nurse — who often works part-time, one analysis found.

“State and local public health departments are decimated resource-wise,” said Lurie, who is now an executive director at an international organization, the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations. “You can’t expect them to do the job if you only resource them once there’s a crisis.”

Another explanation is a lack of urgency because the virus hasn’t severely harmed anyone in the country this year. “If hundreds of workers had died, we’d be more forceful about monitoring workers,” Chessher said. “But a handful of mild symptoms don’t warrant a heavy-handed response.”

All the bird flu cases among U.S. farmworkers have presented with conjunctivitis, a cough, a fever, and other flu-like symptoms that resolved without hospitalization. Yet infectious disease researchers note that numbers remain too low for conclusions — especially given the virus’s grim history.

About half of the 912 people diagnosed with the bird flu over three decades died. Viruses change over time, and many cases have probably gone undetected. But even if the true number of cases — the denominator — is five times as high, said Jennifer Nuzzo, director of the Pandemic Center at Brown University, a mortality rate of 10% would be devastating if the bird flu virus evolved to spread swiftly between people. The case fatality rate for covid was around 1%.

By missing cases, the public health system may be slow to notice if the virus becomes more contagious. Already, delays resulted in missing a potential instance of human-to-human transmission in early September. After a hospitalized patient tested positive for the bird flu virus in Missouri, public health officials learned that a person in the patient’s house had been sick — and recovered. It was too late to test for the virus, but on Oct. 24, the CDC announced that an analysis of the person’s blood found antibodies against the bird flu, signs of a prior infection.

CDC Principal Deputy Director Nirav Shah suggested the two people in Missouri had been separately infected, rather than passing the virus from one to the other. But without testing, it’s impossible to know for certain.

The possibility of a more contagious variant grows as flu season sets in. If someone contracts bird flu and seasonal flu at the same time, the two viruses could swap genes to form a hybrid that can spread swiftly. “We need to take steps today to prevent the worst-case scenario,” Nuzzo said.

The CDC can monitor farmworkers directly only at the request of state health officials. The agency is, however, tasked with providing a picture of what’s happening nationwide.

As of Oct. 24, the CDC’s dashboard states that more than 5,100 people have been monitored nationally after exposure to sick animals; more than 260 tested; and 30 bird flu cases detected. (The dashboard hasn’t yet been updated to include the most recent cases and five of Washington’s reports pending CDC confirmation.)

Van Kerkhove and other pandemic experts said they were disturbed by the amount of detail the agency’s updates lack. Its dashboard doesn’t separate numbers by state, or break down how many people were monitored through visits with health officials, daily updates via text, or from a single call with a busy farm owner distracted as cows fall sick. It doesn’t say how many workers in each state were tested or the number of workers on farms that refused contact.

“They don’t provide enough information and enough transparency about where these numbers are coming from,” said Samuel Scarpino, an epidemiologist who specializes in disease surveillance. The number of detected bird flu cases doesn’t mean much without knowing the fraction it represents — the rate at which workers are being infected.

This is what renders California’s increase mysterious. Without a baseline, the state’s rapid uptick could signal it’s testing more aggressively than elsewhere. Alternatively, its upsurge might indicate that the virus has become more infectious — a very concerning, albeit less likely, development.

The CDC declined to comment on concerns about monitoring. On Oct. 4, Shah briefed journalists on California’s outbreak. The state identified cases because it was actively tracking farmworkers, he said. “This is public health in action,” he added.

Salvador Sandoval, a doctor and county health officer in Merced, California, did not exude such confidence. “Monitoring isn’t being done on a consistent basis,” he said, as cases mounted in the region. “It’s a really worrisome situation.”

KFF Health News regional editor Nathan Payne contributed to this report.

Comments are closed.